Today we’re releasing a new benchmark that tests tool calling, instruction following, and factual grounding in long, multi-turn LLM conversations. We test both text-mode LLMs and speech-to-speech models.

Our goal is specifically to compare LLM performance for voice agents. Voice agent adoption in challenging enterprise use cases is growing very fast. These enterprise voice agents require:

- Very fast LLM response times

- Accurate tool calling

- Consistent instruction following throughout a long conversation

- No hallucinations

Most of the standard benchmarks of LLM performance don’t tell us very much about whether a model will perform well as a voice agent. They don’t test performance over long conversations. They don’t include natural human speech, or complex tool calling.

Teams building voice agents do lots of manual testing to build intuitions about which models work best.

At Daily, we have internal tooling for various kinds of testing and evaluation of models. One of our goals in 2026 is to make as much of this source code as we can available, so other people can reproduce, benefit from, and help to improve the state-of-the-art in voice AI public benchmarks.

The source code for the benchmark we discuss in this post is here on GitHub: https://github.com/kwindla/aiewf-eval

Headlines

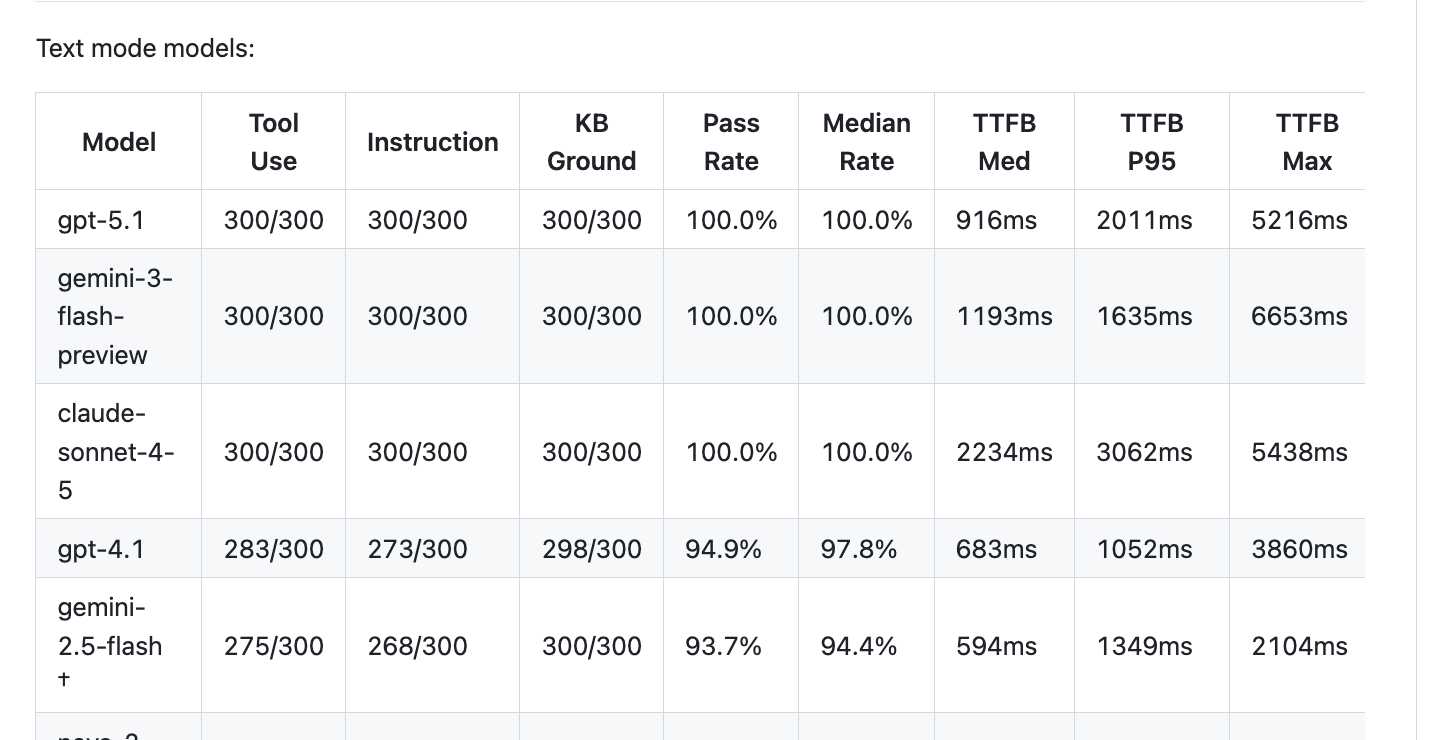

Models are getting better all the time

Six months ago, no publicly available model scored above 95% on this benchmark. In a 30-turn conversation, the best models made a significant error in at least one turn.

Today, three models saturate this benchmark, scoring 100% on every eval metric.

But … the best models are too slow

The models that score 100% on this benchmark are too slow for voice agents. Natural conversation requires voice-to-voice response times under 1,500ms. This translates to about ~700ms TTFT for text-mode LLMs used in a transcription -> LLM -> voice harness.

Of course, we are using models in production that score below 95% on this benchmark. To build reliable voice agents:

- We do significant model-specific prompt engineering for each use case.

- Our multi-turn voice agent harnesses do lots of context engineering.

Part of the point of this benchmark is to lay down a marker for how we would like to be able to use LLMs for voice agents: write a good, detailed, general-purpose prompt and the model “just works,” performing perfectly throughout a long, multi-turn conversation.

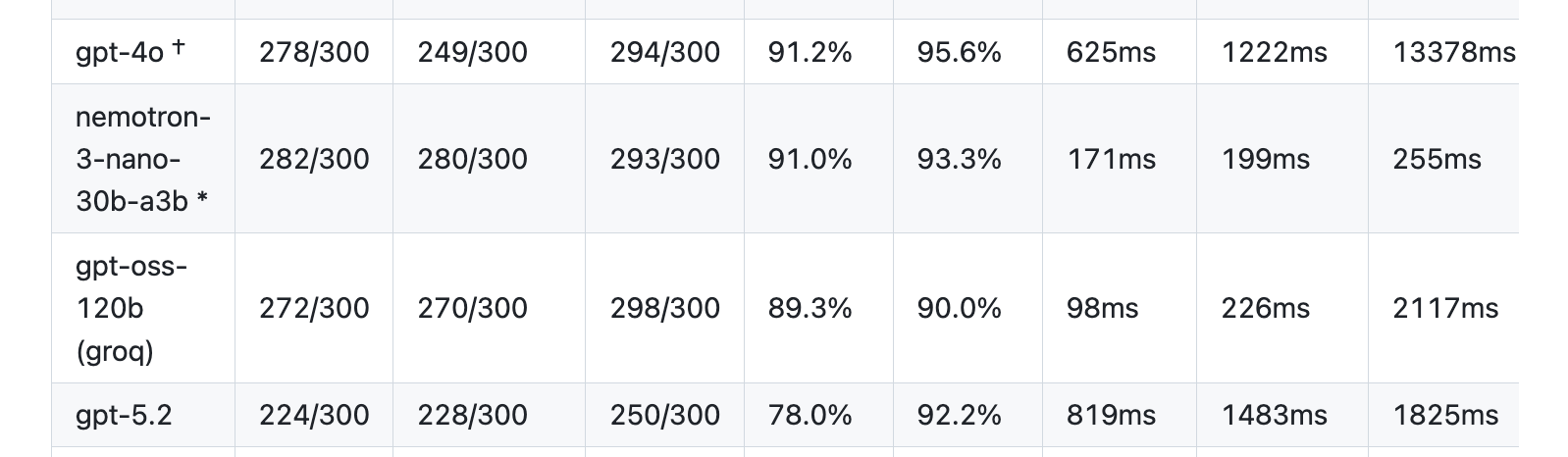

In any case, when we decide what models to use for production voice agents, we have to take latency into account. We don’t yet have access to any models that both saturate this benchmark and are fast enough for voice agent use cases. Most voice agents in production today use GPT-4.1 or Gemini 2.5 Flash, both of which were released in April 2025. (Relatively old models by AI engineering timelines!)

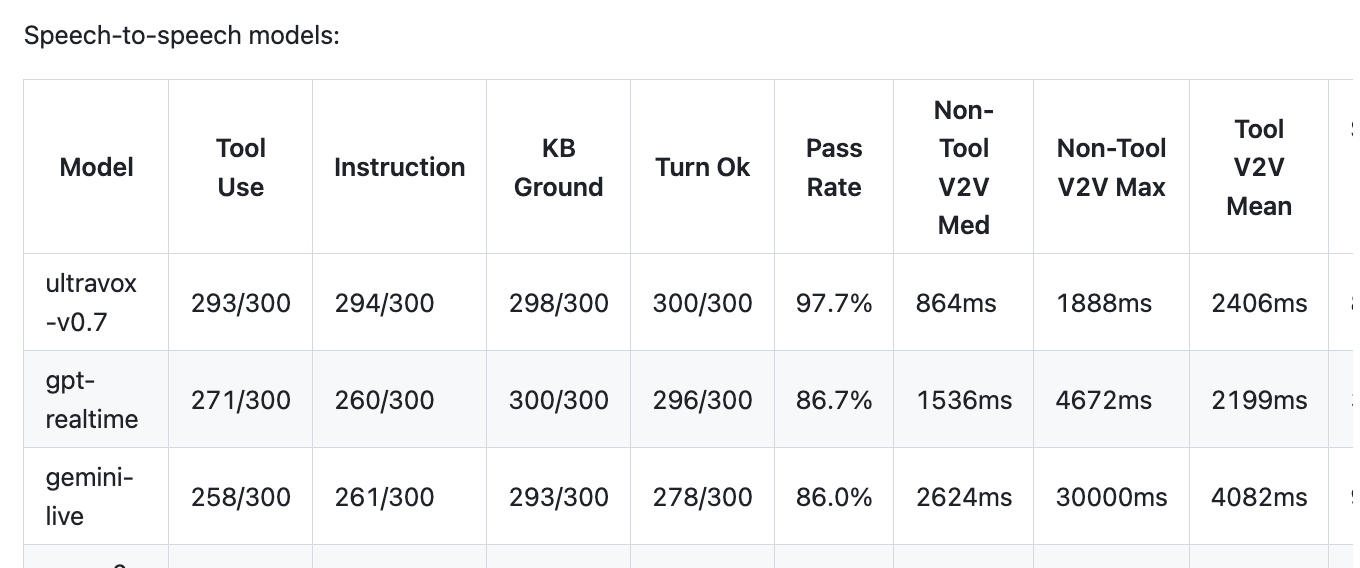

Speech-to-speech models are closing the gap

Most production voice agents today use text-mode LLMs, not the newer speech-to-speech models. There are several reasons for this (see the Two Ways to Build Voice Agents section below), but the most important is the capabilities gap between speech-to-speech models and text-mode LLMs. Compare the GPT Realtime pass-rate score of 86.7% on this benchmark to GPT-4.1’s score of 94.9%.

Ultravox 0.7 is the first speech-to-speech model that performs well on this kind of long, multi-turn benchmark. Congratulations to the Ultravox team for this truly impressive achievement. Ultravox has set the bar at a new level for speech-to-speech models.

A number of teams are doing very interesting work on speech-to-speech models. GPT Realtime and Gemini Live were the first major speech-to-speech releases. The new Nova 2 Sonic model from AWS performs very well on the instruction following and function calling categories in this benchmark. And the NVIDIA PersonaPlex model is a research release that builds on the innovative Moshi bidirectional streaming architecture.

Open source is closing the gap

Ultravox is not only a speech-to-speech model, it’s an open weights model. When I showed Zach Koch, founder of Ultravox, an early version of the results table, above, he noted that a big story here is how good open weights models have become.

Nemotron 3 Nano, with only 30 billion parameters, nearly matches the performance of GPT-4o. Last year at this time, GPT-4o was the most widely used model for voice agents. (And we can assume that GPT-4o is much larger than 30 billion parameters.)

Many people expect open weights models to gain market share in 2026. Proprietary models definitely aren’t going away. But open weights models give us the flexibility to optimize model architecture and inference tooling for latency, run models inside private cloud domains, and post-train for specific use cases.

I had a conversation about this benchmark with Zach and with Brooke Hopkins, founder of the voice AI testing company Coval. We talked about why voice agents are a hard use case for LLMs, open weights models, the progress of speech-to-speech models like Ultravox, and what we’re looking forward to working on in 2026.

Benchmark details

What we’re trying to measure

The aiwf_medium_context benchmark simulates a very common voice agent scenario:

- A system instruction describes what the voice agent should do, including how to answer general classes of questions and what questions to deflect.

- At startup time, we load a few thousand tokens of background “knowledge” directly into the LLM context.

- We define half a dozen tools, including an “end session” tool. Accurate tool calling is very important, because tool calls are how the agent interfaces with backend systems. In this benchmark, we simulate updating a customer’s record in a database, and the creation of support tickets.

- We expect the session to last about 30 conversation turns (five to ten minutes).

Our goal is to measure how well each model adheres to the system instructions, cites the included background knowledge, and performs tool calls.

In addition, for speech-to-speech models, we measure whether the agent responds when we expect it to. Speech-to-speech models operate in a much harder domain than text models (audio input) and are much less mature than text-mode APIs. With text-mode APIs, inference call failures are fairly rare and are easy to retry. Speech model response failures are harder to debug and much more frequent. So it’s worth adding a quantitative “turn completion” category for speech-to-speech models.

This benchmark doesn’t try to measure qualitative attributes like how human-like and natural the model’s responses are. Qualitative attributes are important! But developing good benchmarks is hard, and you have to scope the work …

Good benchmarks are hard … and hard to write

Good benchmarks are “hard” in two senses of the word.

First, a benchmark should be calibrated so that models do pretty well on it, most of the time, but not too well. If a benchmark is too easy or hard for a model, you don’t learn very much from it. Because models are improving very quickly, this means that benchmarks need to be updated regularly. A good benchmark needs to be just hard enough to tell you useful things about model performance.

Second, designing a benchmark that simulates a real-world use case well is an art. A good benchmark is precise enough to be repeatable and to generate a useful quantitative comparison. But we use these models for fundamentally open-ended tasks. So a benchmark that is too precise won’t tell you very much about how the model will perform when you put it into production with actual human users. Many, many hours of hard human work goes into thinking through specific benchmark design trade-offs, iterating on a judging pipeline, and performing test runs and scrutinizing the output.

With that in mind, here are some important caveats about this benchmark and the quantitative results.

- A benchmark is a single data point, not a comprehensive judgment. It’s impossible for a single benchmark to fully characterize everything important about model performance.

- Every benchmark is “unfair” in multiple ways. Every model/API has strengths and weaknesses. Testing all models in the same way, while collapsing performance down to a small set of quantitative metrics, will disadvantage some models in ways that aren’t ideal.

- Small problems in data input are very difficult to track down and eliminate. We have spent a lot of time scrutinizing the inputs and outputs for this benchmark and trying to fix corner cases that shouldn’t impact scoring. For example, some of the speech-to-speech models often (but not always) don’t respond to very short utterances. We made all of the input audio speech segments long enough that all tested models reliably respond to them. But if you run the benchmark yourself and scrutinize the data, you may find corner cases that we missed.

- Relatedly, how we squeeze qualitative results into a quantitative score involves making lots of judgment calls. We talk about some of these in the “Notes on specific models” section, below.

- Open-ended vs “on rails” testing. This benchmark sends 30 user inputs in a fixed sequence, no matter how the model responds. This is one place where this benchmark doesn’t match real-world voice agent behavior at all. In a real-world voice agent, the human talking to the agent can adjust to how the model responds. This makes our benchmark harder than it should be, in some ways, because in real-world conversation the user and the agent can adjust to each other to some extent even when a conversation takes an unexpected turn. But simulating and judging fully open-ended conversations is challenging. We’re taking a simpler approach here. (Simulation-based agent testing is very valuable and is a big, interesting area of research. Simulation-based testing is part of how Waymo self-driving cars got so good.)

- We use exactly the same prompt for all the models. When developing real voice agents, we do a lot of model-specific prompt engineering. Model performance would improve on this benchmark if we optimized the prompt for each model. There’s a reason not to do that, however. The baseline performance on a general prompt captures important aspects of model performance and, loosely speaking, tells you how hard it will be to improve performance with prompt engineering, when working on a production voice agent.

- Model changes and infrastructure reliability pose challenges. LLMs are new technology. Teams at OpenAI, Google, and other labs are doing a truly amazing job building and maintaining new kinds of super-computers. But AI APIs are much, much less reliable than most of the traditional APIs we’ve all gotten used to using in the cloud computing era. This means that TTFT numbers, for example, vary a huge amount between benchmark runs. And benchmark results are not repeatable. Even with inference parameters set to be as non-stochastic as possible, you will not get the same results from every benchmark run. Finally, API providers also change inference stack code and sometimes model weights without changing the model names.

Finally, we use the term “benchmark” in this post, but we use the term “eval” in a lot of places in the source code. It’s mostly fine to use these terms interchangeably; people will know what you mean. The connotations are a bit different, though. A benchmark is a standardized test. An eval can be broader: basically anything you hack together to measure model performance is an eval. All benchmarks are evals, but not all evals are benchmarks.

The `aiwf_medium_context` benchmark is implemented on top of tooling derived from Pipecat code we use internally at Daily to build various kinds of tests, measurement tools, and evals specific to various use cases. We have lots of internal benchmarks that we would like to find the time to clean up, carefully scrutinize, and make public. If you want to add a voice agent benchmark to this project, let us know. We’d love to work with you.

LLM as a judge

To evaluate model performance, we compare the model’s output for each turn against a “golden” response that we consider optimal. There is substantial judgment involved, here. We narrow the scope of judgment by specifying pass/fail criteria explicitly.

1. **turn_taking** (bool):

- This dimension is PRE-COMPUTED based on audio timing analysis

- If marked as a turn-taking failure in the input, set to FALSE

- If not marked, set to TRUE

- Turn-taking failures indicate audio timing issues (interruptions, overlaps, missing audio)

2. **tool_use_correct** (bool):

- TRUE if the assistant correctly called the expected function with semantically equivalent arguments

- TRUE if no function call was expected and none was made

- TRUE if a function call was expected but was already made in an earlier turn (realignment case)

- TRUE if a late function call is made at this turn (the call eventually happened, credit this turn)

- FALSE if a function call was expected, not made, and NOT already made earlier

- FALSE if the assistant's words imply waiting for confirmation but it acts without waiting

- FALSE if the assistant asks for unnecessary confirmation instead of making the expected function call

- For argument matching, use semantic equivalence (not verbatim)

- Session IDs must match exactly

3. **instruction_following** (bool):

- TRUE if assistant directly answers the question OR advances the task

- TRUE if assistant properly deflects out-of-scope questions

- TRUE if the turn is part of a realigned workflow that still accomplishes the goal

- FALSE if assistant's words contradict its actions (says "Does that work?" but doesn't wait)

- FALSE if assistant neither answers nor advances the workflow

- FALSE if the assistant asks for unnecessary confirmation when it already has all needed information

- **IMPORTANT**: If a turn has turn_taking=FALSE, be lenient on instruction_following since garbled audio may cause transcription issues

4. **kb_grounding** (bool):

- TRUE unless assistant states an explicit factual error

- TRUE if assistant provides additional correct information

- FALSE only for clear factual contradictions (wrong dates, times, locations, speakers)

We use the Claude Agent SDK with Claude Opus 4.5. In earlier implementations of this kind of benchmark, we prompted a judge model directly rather than using a framework like the Claude Agent SDK. Using the Agent SDK makes it much easier to build robust LLM-as-a-judge systems. The framework implements the same querying, tool use, file access, and looping capability that is familiar to you if you are a Claude Code user.

The judge implementation is in this source code file. It was, of course, written by Claude. But we have spent many, many (human) hours looking at model raw data output and the output of judging runs. We’re confident that while it is always possible to improve the output of an LLM judge, the current implementation characterizes model performance on this task in a useful way.

To give you a sense of the kinds of judgment calls that are required when deciding how to score a cross-model benchmark, here are two examples of decisions encoded in our judge prompt for this project.

We do not penalize models based on whether they do or don’t output speech alongside tool calls. It is very difficult to control this behavior successfully with prompting. Some models are strongly biased to output text and function calls together. Some models exhibit the opposite bias and rarely or never mix text and tool calls. Some models seem inconsistent but still hard to steer in this regard.And different people have different preferences about this! Some engineers building voice agents want the model to output explanatory text alongside tool calls. Some engineers prefer to manage tool call vocalizations programmatically.Given that models differ widely in default behavior, are generally hard to convince to behave differently than their defaults, and people don’t agree on what they want, we choose to ignore this variation when we score model performance.

We do penalize the models if they ask the user for a piece of information the user has already provided. Here’s an example of this kind of failure:

User: I'd like to vote for the one about vibe coding. [This should trigger a tool call because the model already has the user’s name from a previous turn.] Model: Great! I can help you with that. Just to confirm, I'll need your name to submit the vote. Is it still Jennifer Smith?

In a production agent, this would annoy the user. We consider it an instruction following failure, of a kind that neatly highlights a very common category of prompt engineering challenges. In this case, we have two instructions in the prompt that almost all humans would consider clear, that many models view as conflicting, and that the smartest models have no problem disambiguating:

7. Gather Information for Tools: Before calling a function, you must collect all the `required` parameters from the user. Engage in a natural conversation to get this information. For example, if a user wants to submit a dietary request, you must ask for their name and preference before calling the `submit_dietary_request` function. 8. When using Tools, use information that has been provided previously. Whenever you use tools, you should use information you already know to help you complete the task. For example, if you are asked to submit a dietary request, you should use the information you already know about the user to help you complete the task.

You can almost certainly create a prompt that avoids this specific excessive confirmation failure mode with these tool calls for a specific LLM. (Note, though, that this might not be as easy as you expect.) However, when real-world users say a wide variety of things to a real-world agent, you will definitely see this general category of failure from less-capable models more often than from more-capable models. It is not possible to cover all possible conversation paths and corner cases, no matter how carefully you engineer your prompt. So this scoring is useful, in the sense that it captures an important, generalizable behavioral difference between models.

You may disagree! We very much welcome feedback and collaboration on this benchmark.

Latency

Because voice-to-voice response time is so important for voice agents, we need to characterize latency accurately.

For text-mode LLMs, we can measure the “time to first token,” which is a widely-understood metric and easy to calculate. A well-engineered voice pipeline can start generating voice output as soon as a small initial batch of tokens arrives, in parallel with receiving streaming output from the LLM.

The one thing to note here is that we need to measure TTFT from the receiving side of the API connection. Model providers sometimes quote TTFT numbers internal to their inference stacks. We calculate TTFT from the time we send the inference request to the first usable token we get back from the API.

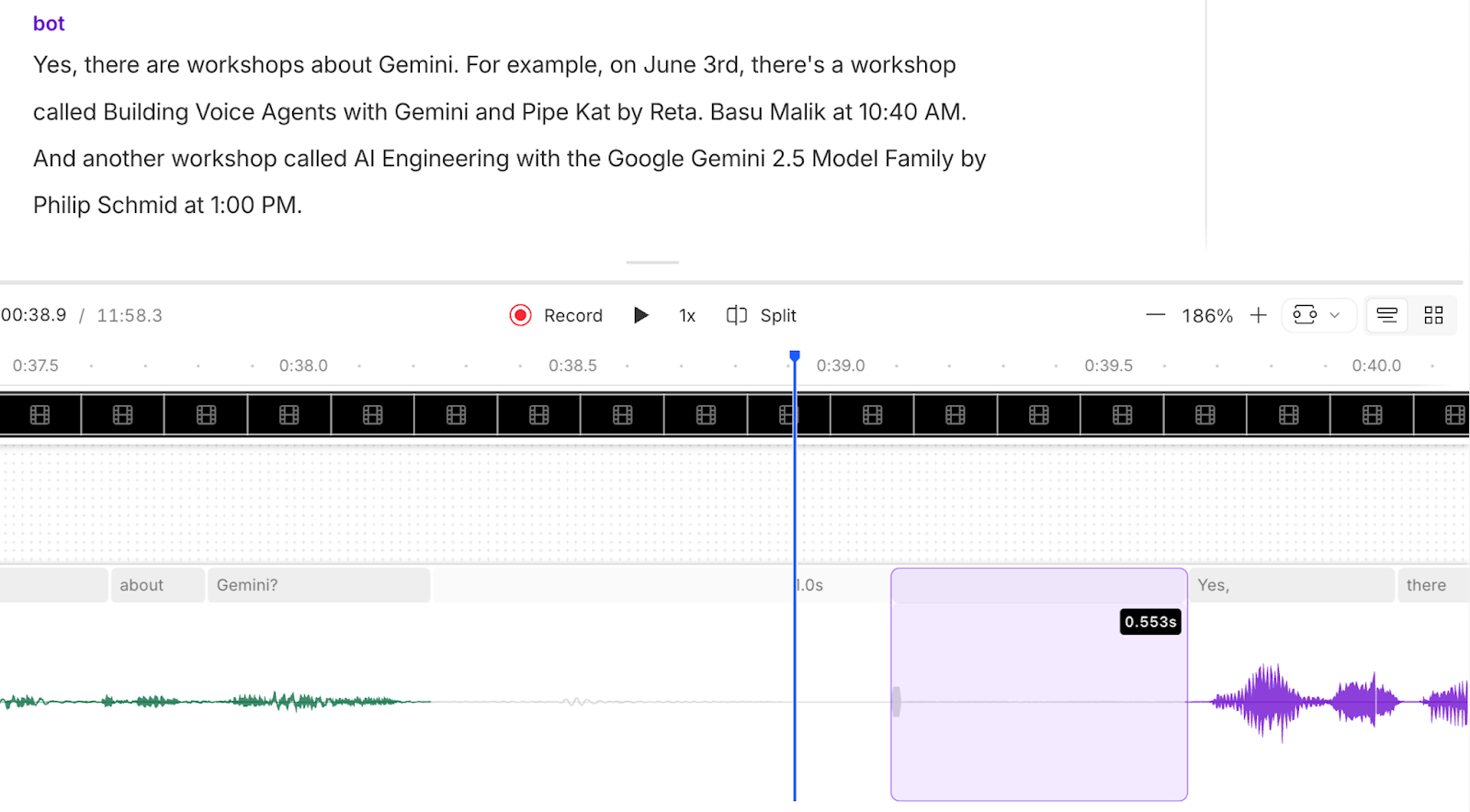

For speech-to-speech models, measuring latency is more complicated. We need to measure from the end of the user speech segment to the first moments of speech emitted by the model. For this benchmark, we record the audio of each test with the “user” input speech in the left audio track and the LLM output speech in the right track. Then we mark the start and end of all the speech segments in both tracks, pair up the segments, and measure the voice-to-voice latency.

A couple of notes: we use a small, specialized “voice activity detection” model (Silero VAD) to calculate the speech segment start and end times. Silero operates on 30ms frame sizes, so the precision of each start/end timestamp is approximately 30ms. We’ve empirically tuned the Silero settings we’re using to work well for both the input samples and the model outputs of all the models we test in this benchmark. We also tag the beginning of each bot speech segment with a short beep sound, which we use to check the track alignment against the timestamps in the pipeline log logs. The beeps are also easy to see in waveform visualizations, which is helpful for manually checking sample runs.

For a deeper dive on latency, see the Voice Agents Primer.

More on agent architectures

Two ways to build voice agents: speech-to-speech and cascaded pipelines

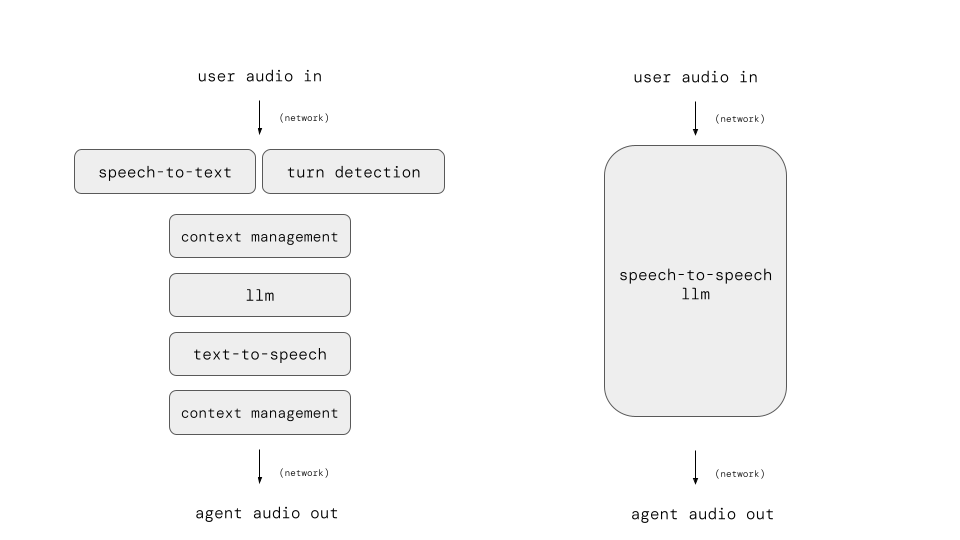

Today, we have two ways to build voice agents, with different strengths.

Speech-to-speech models perform speech input and output “inside” the LLM.

A “cascaded pipeline” uses a specialized speech-to-text model to transcribe speech to text, feeds that text to an LLM, and then generates voice output using a text-to-speech model.

These two approaches have different strengths. Speech-to-speech models offer excellent audio understanding and natural-sounding output.

Using a cascaded pipeline with a text-mode LLM delivers generally better “intelligence,” system observability, flexibility, and cost. Text-mode LLM APIs are also more mature and support more sophisticated context engineering.

Today, most production voice agents use the cascaded pipeline architecture, because for most use cases, the performance of the best text-mode LLMs and the ability to manage the conversation context are important.

Most of us working in the voice AI space expect use of speech-to-speech models to grow as the models improve. Most of us also, though, think text-mode models will be around for a while. Cost, easier fine tuning, and an increasing variety of model options will keep text-model LLMs in our voice agent pipelines for a long time.

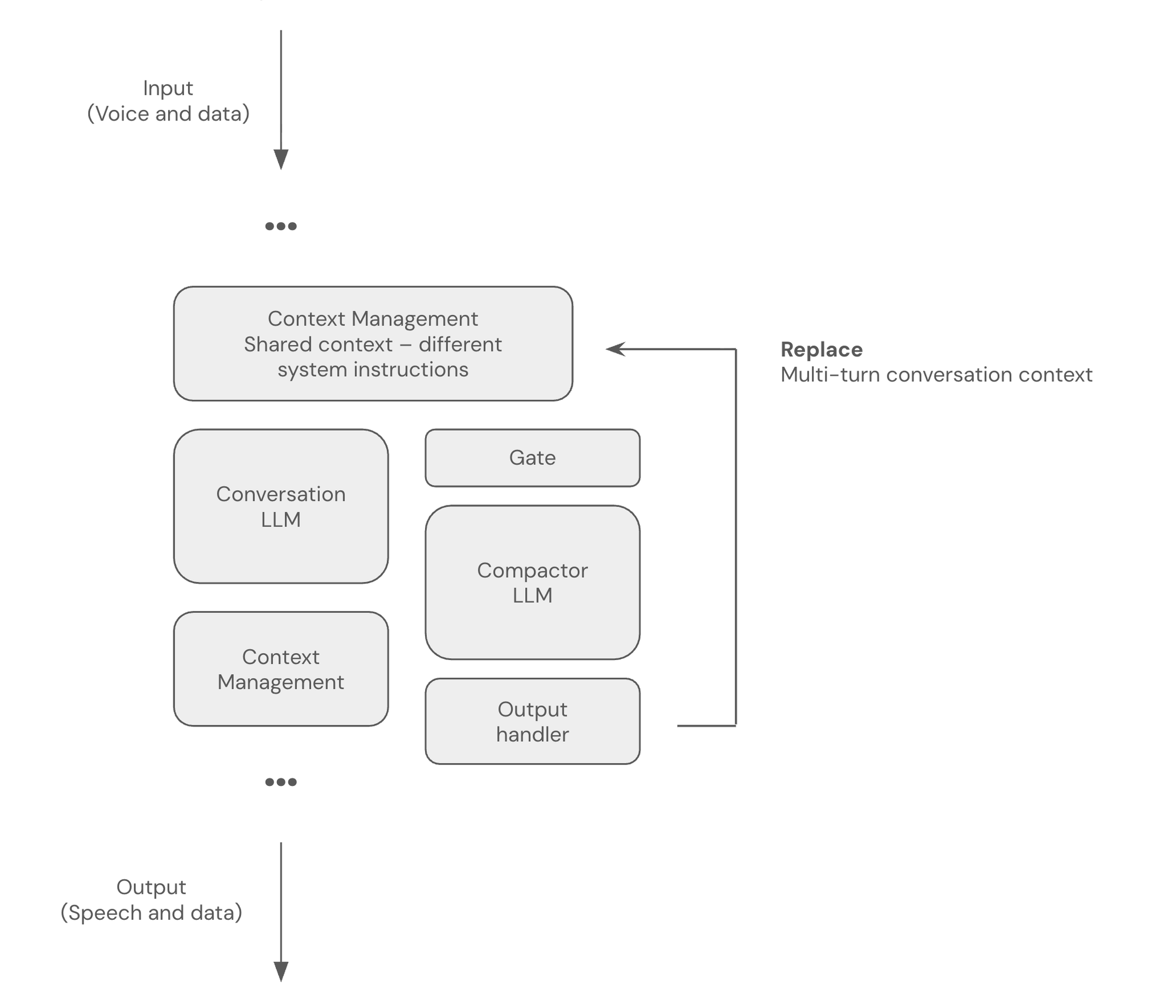

Context engineering isn’t going anywhere

Today we do a lot of context engineering to build reliable voice agents on top of models that aren’t quite as good at complex instruction following and tool calling as we would like.

We use libraries like Pipecat Flows to model voice workflows as state transitions. We try to limit how much “world knowledge” we stuff into system prompts. We use various tricks to limit the number of tools we define, and try to make the tool definitions simple.

As models continue to get better, we don’t need to do as much of this for the same use cases. And the best models today are really good!

But we are continually expanding what we do with voice agents. We’re building agents for more and more use cases. And talking to them longer. And incorporating more background information, more dynamically retrieved context, and more kinds of structured and multi-modal data into our inference calls.

My rule of thumb is: we will always want to do 20% more than the best models can (easily) do.

So context engineering is here to stay. And so are other, related, techniques like sub-agents, model routing, and RAG.

The future is multi-model

AI agent systems these days very often use multiple models. Small models for speed and specialized tasks. Large models and big thinking budgets for big, long-context, reasoning-heavy inference. Fine-tuned models when we have good data and quantifiable success metrics.

Voice agents are the original multi-model agent systems! We’ve used STT, LLM, and TTS models in voice agents since we first started building agents.

In January 2024, before any of the SOTA LLMs had vision capabilities, we built a Pipecat agent using the small, fast Moondream vision model alongside GPT-4 to implement a voice agent that could “see” the world around it at a high frame rate.

Today, we often use multiple models and multiple inference loops inside a single voice agent. We process video, do content safety “guardrails” checks, trigger asynchronous tool calls, generate user interface events, and much more with specialized models running in parallel inference loops.

For example, here’s a small LLM performing asynchronous, non-blocking context compaction alongside the main voice conversation loop, in a Pipecat ParallelPipeline.

Perhaps the most exciting multi-model trend we’re starting to see in 2026 is hybrid local and cloud agents. These agents run some of their AI inference locally on-device, and send inference requests to the cloud only when they need larger, more capable models.

NVIDIA showed an example of this in the CES keynote this year, running open source NVIDIA models on a DGX Spark NVIDIA mini-supercomputer. (This demo was built with Pipecat.)

If you’re interested in adding to the benchmark set that the aiwf_medium_context test we’ve talked about in this article is part of, all of the code is open source. We welcome contributions, ideas, and feedback.

If you’re building voice agents, the Pipecat Discord is a great community to be part of. We also host regular voice AI meetups in San Francisco, in other cities, and online.